Variable apes

Species: Northern white-cheeked gibbon (Nomascus leucogenys), among others

Genome size: 2.94 billion base pairs

The gibbon, the last ape to have its genome sequenced, tolerates a surprising number of chromosome rearrangements. The sequence, published today (September 10) in Nature, reveals that gibbon genes involved in chromosome segregation are rich in repetitive sequences called LAVA elements. Such chromosome shifts are known to cause cancer or birth defects in humans, making the gibbon genome a valuable resource for further study.

“We do this work to learn as much as we can about gibbons, which are some of the rarest species on the planet,” lead author Lucia Carbone of the Oregon Health & Science University said in a press release. “But we also do this work to better understand our own evolution and get some clues on the origin of human diseases.”

The gibbon genome provides insights into the evolutionary history of this most diverse group of apes. The researchers sequenced eight of the 12 or more species of gibbons. Their analyses suggest that the four genera of gibbons diverged nearly simultaneously about 4 million years ago. This diversification likely coincided with rising sea levels and changes in tropical forest habitats, which may have led to the isolation and subsequent speciation of different groups.

Species: Robusta coffee (Coffea canephora)

Genome size: 710 million base pairs

Coffee is the latest essential crop to have its genome sequenced. The draft assembly, published last week (September 5) in Science, provides insights into genes that give the plant’s seeds their distinctive flavors and caffeine content. Scientists prioritized Coffea canephora for sequencing over the more widely grown C. arabica, which has a more complicated genome, as it originated from the hybridization of C. canephora with C. eugenioides.

“The coffee genome helps us understand what’s exciting about coffee—other than that it wakes me up in the morning,” study coauthor Victor Albert of the University at Buffalo, New York, said in a press release. “By looking at which families of genes expanded in the plant, and the relationship between the genome structure of coffee and other species, we were able to learn about coffee’s independent pathway in evolution, including—excitingly—the story of caffeine.”

Indeed, the researchers found an abundance of genes encoding N-methyltransferases (NMTs), enzymes critical for the synthesis of caffeine. Coffee’s NMT genes are more similar to other coffee genes than to the NMTs of tea and cacao, suggesting that caffeine production evolved independently in the three lineages.

The team also identified pathogen-defense genes that could aid efforts to develop plants resistant to coffee leaf rust, a significant problem in Central America in recent years.

Checkered history

Species: Glanville fritillary (Melitaea cinxia)

Genome size: 390 million base pairs

The Glanville fritillary, an orange and black “checkerspot” butterfly native to Europe and temperate Asia, joins the silkmoth Bombyx mori and the Postman butterfly Heliconius melpomene as the third sequenced species in the order Lepidoptera. The fritillary has 31 chromosomes; sequencing its genome enabled scientists to confirm this as the ancestral lepidopteran chromosome number. The work was published last week (September 5) in Nature Communications.

A comparison of the three species showed that 96 percent of their genes are found at orthologous chromosomal positions—a remarkable degree of conservation, according to study author Mikko Frilander of the University of Helsinki’s Institute of Biotechnology. “The most astonishing thing is that it seems like the genes have stayed in the same chromosomes practically throughout the evolutionary history of butterflies—at least for 140 million years. Such stability is nearly unique among all organisms,” Frilander said in a press release. “What is even more surprising is that even though some chromosomes have fused during the lepidopteran evolution, the genes remain on their own side of the chromosome even after chromosomal fusions.”

The M. cinxia genome sequence allowed Frilander and his colleagues to reconstruct the probable chromosome fusions that created the 28 and 21 chromosomes in B. mori and H. melpomene, respectively. The fusions may be a result of lepidopterans’ unstable holocentric chromosomes, which attach to spindle microtubules along their full length during cell division, as opposed to monocentric chromosomes that connect only at their centromeres.

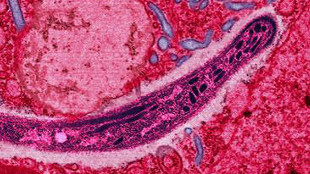

Bloody trickster

Species: Chimpanzee malaria parasite (Plasmodium reichenowi)

Genome size: 24 million base pairs

The parasite that causes most human malaria, Plasmodium falciparum, evolved from species that infect African great apes. Now, the first full genome sequence of an ape-pathogenic malarial species points to subtle variations that may determine host specificity. The P. reichenowi sequence was published this week (September 9) in Nature Communications.

Although the human and chimpanzee pathogens share a similar set of around 5,500 genes, researchers found differences in genes that allow the parasites to overrun red blood cells and evade the host immune system. However, the copy numbers and arrangements of these genes are largely preserved between the two species.

“Discovering that the key differences lie in genes responsible for red blood cell invasion reassures us that we’ve been looking in the right place,” Thomas Otto of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in the U.K., who led the study, said in a press release. “Researchers have identified surface proteins as promising vaccine candidates already; and our finding adds more support, showing that it is the difference in the parasites’ surface proteins that determine which host it will infect.”

Three-quarters of the 100 most divergent genes have unknown functions, “highlighting that the least explored content of the genome includes genes that may have important roles relating to host differences,” the authors wrote in their paper. “This work therefore immediately identifies a number of new genes for which functional work is urgently required.”

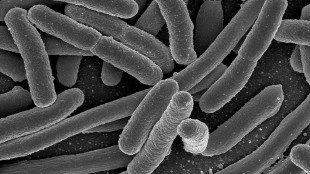

E. coli exposed

Species: Escherichia coli O157:H7 Strain EDL933

Genome size: 5.55 million base pairs

A strain of enterohemorrhagic E. coli known for causing outbreaks of food poisoning associated with ground beef has now been fully sequenced. The work, published last month (August 14) in Genome Announcements, closes gaps and clears up ambiguous base calls in the sequence originally published in 2001.

The genome of EDL933 is replete with prophages—integrated segments of bacteriophage genomes. These sequences are highly repetitive and unstable, allowing the bacteria to nimbly gain new virulence traits or antibiotic resistance, but making the genome devilishly difficult to fully sequence. Today’s single-molecule sequencing technology, however, enabled the researchers to close gaps in the genome of EDL933 due to such repetitive sequences; high-coverage short reads finished the job.

“New sequencing and assembly methods are enabling a full expose of pesky pathogens; there is no place to hide genetic characteristics anymore,” study author Bernhard Palsson of the University of California, San Diego, said in a statement. “The full genetic delineation of multiple pathogenic strains is likely to not only improve our understanding of their characteristics, but to find and exploit their vulnerabilities.”

The EDL933 strain was first isolated from hamburger meat linked to food poisoning cases in Michigan in 1982, but is best known for causing a 1993 outbreak at Jack-in-the-Box restaurants in the western U.S.

RSS